Foreword:

This is the first post of what I hope will become an ongoing series on the nature of despair. What I envisage is to introduce a work of art – be it imagery, poetry, music, film or novel – that was created from the darkest places of the soul. Darkness and despair have been a part of my life since my early teens, and as I have grown accustomed to it, and rediscovered joy in the midst of it, I have become inextricably marked by depression, and to this day there is nothing in the world so comforting as a warm, dark corner where no one can see me, My Dying Bride playing in the background, and a glass of wine reflecting the candlelight.

Being a musician and composer by training, many of these tales are likely to revolve around songs, symphonies and albums. However, I hope to reach out to further art forms, and discover among the canon of literature, film and imagery endless tales of despair.

The Tragedy of the Symphony Pathétique

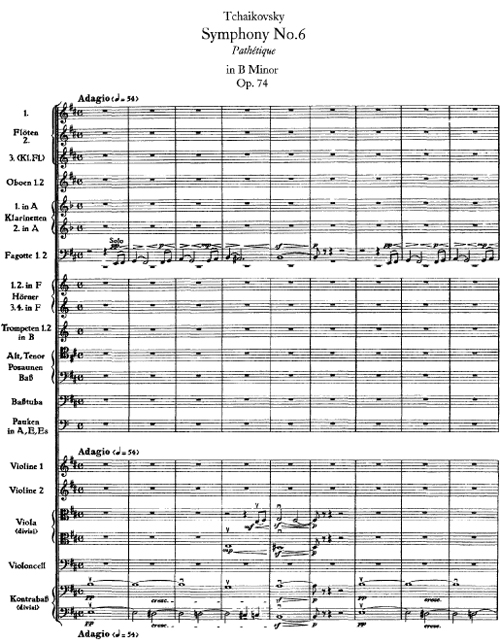

There is in my mind no more fitting work of art more wrought with despair than Pyotr Illyich Tchaikovsky’s sixth symphony, popularly known as the Pathétique (in Russian, Patetičeskaja). This is a piece of music that passes through a sea of emotions of an intensity beyond anything I have heard or seen in my life. From the moodiness of the opening to the fury of the first movement’s climax, the calm sadness of the lilted waltz to the dizzying madness of the third movement, and ultimately the chilling, profoundly bleak finale, in fifty minutes this symphony takes the listener through a world of thought and a lifetime of tragedy.

The symphony’s name derives from the Russian word for passion, not pity, and it is a just name. The deep and overwhelming sadness of this music, however, is how closely it ties to Tchaikovsky’s turbulent personal life. Six days after its world première, Tchaikovsky died. He claimed to his brother that the symphony was steeped in meaning, but he would not reveal the music’s subject to anyone. Some have since said that it was his final death letter.

Tchaikovsky’s own life was a mirror for this tragedy. His sorrows began with the death of his mother at the age of fourteen, and from that day onwards he succumbed to a cloud of depression that even the recognition he eventually garnered could not completely break him free of. His life was a tale of abandonment, despair and frustration; Though homosexual, the social convictions of Victorian Russia prevented him not only from being open about this, but even from acknowledging it in his own mind. He suffered two affairs, both of which ended with the woman he cared for leaving him. He did eventually marry, but they lived together for less than two months, and she eventually bore children from another man.

Even the one light of hope – his patron, Nadezhda, with whom he corresponded for thirteen years in over a thousand letters – ceased communication with him in 1890, and he remained hurt, bitter and bewildered over this for the remaining three years of his life.

Tchaikovsky died in 1983 by his own hand. Perhaps he had become overwhelmed by the depth of despair into which his life had sunk; perhaps he could no longer bear the terrible conflict of his sexuality, which culminated in an attempted affair with his own nephew. On the night of the première of the sixth symphony, Tchaikovsky drank a glass of unboiled water, contracted cholera, and died six days later.

The terrible pain, sadness and despair is overwhelmingly prevalent in this symphony. Before his death, Tchaikovsky confided to his brother that the symphony was full of a deeper meaning, but would not say what it was. After he died, his brother realized he had been speaking of his own death – his final symphony, a monument to tragedy, was his suicide note. A parallel for his own life – childhood sadness, angst and fear at odds with the fervor and passion of creativity. Tchaikovsky destroyed more manuscripts than he completed – the artist’s madness refusing to allow him to ever be content with his own music.

This symphony, even out of context, is a tragic and moving musical journey; always a master of emotion, the composer filled his final work with every skill he possessed, and left us thus with his greatest work being his last. When considered as the final cry of a doomed man, a testament to despair, the final, terrible notes of the finale take on the reek of death, and speak of the utter finality of the grave. Tchaikovsky knew as he wrote that this symphony would be his last, and killed himself upon its completion.