The lofty standard to which I hold The Redemption of Erâth is, naturally, Tolkien’s own epic fantasy, The Lord of the Rings. I look to it for inspiration, for guidance, and even, at times, for stylistic advice. It’s an important tome, and influences many of the things that happen in my own work.

I started The Redemption of Erâth as literally a background novella, a short story detailing the history of the world of Erâth, its various Ages, and how it came to be the place of Darkness that it is in the novels themselves. It is, I suppose, the literaly definition of an infodump; it’s purely informational, with little plot or story, and even fewer main characters. It isn’t story; it’s a history book. It might still be interesting to read, and certainly enhances the enjoyment of the main series itself, but is by no means necessary.

However, in the books themselves—Consolation, Exile, and now Ancients & Death, there is a lot of background information that is, if not strictly necessary, at least important to know in order to understand the full impact of the events that take place. In Consolation, much of this takes the form of the ancient legends and tales that Brandyé’s grandfather, Reuel, tells him on winter nights before the hearth. In Exile, there’s a bit of a concentrated backstory element in Chapter 12, The Tale of the Illuèn. It’s essentially a retelling of the fall of Erâth as detailed in History of Erâth. And now, in book three, there’s an entire chapter without characters—only a narrator explaining the major events in the great War of Erâth.

These chapters sometimes feel like roadblocks. As Kirkus Reviews pointed out for Exile:

“The different set pieces of history and myth enrich the story, almost to the point of distracting from the plot, which hovers in place during hefty infodumps.”

—Kirkus Reviews

They go on to say it isn’t all bad, but it still leaves me wondering if—and how—such information can be related to the reader—and if it’s even necessary. Could the plot simply move forward without these chapters?

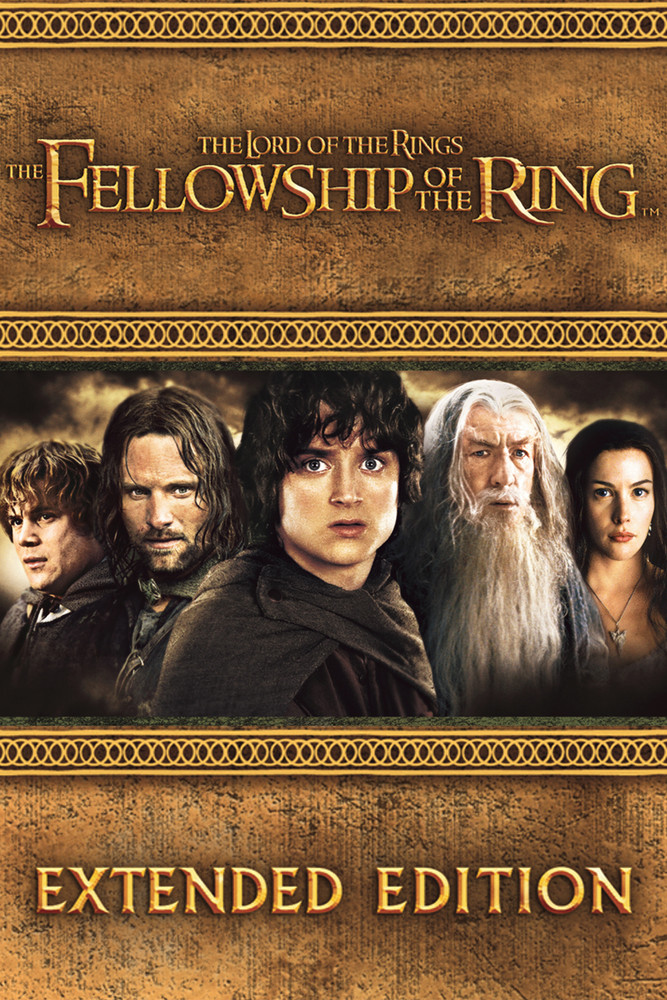

But then I’m reminded of The Lord of the Rings. The second chapter of The Fellowship of the Ring is entitled The Shadow of the Past, and is essentially the same thing: Gandalf relating to Frodo much of the history and events that are important to understand in order to grasp just why the destruction of the One Ring is so vital to the surival of Middle Earth. Tolkien could have arguably just set off with the Ring, having Frodo figure things out over the course of his journey, but instead he chose to pause the story almost before it’s begun, just to make sure the reader is clear on what’s going on.

So when I ask myself if those infodumps in The Redemption of Erâth are a distraction, I think back to my inspiration. If Tolkien thought it was okay, then it’s good enough for me. I might not do it as well as he does, but I just hope it doesn’t stall the plot so stiffly that the reader puts the book down. After all, aren’t epic battles and tales of the fall of kingdoms interesting in their own right?

What do you think? Is it ever okay in a book to just spit out a bunch of background, or should it be more subtely weaved into the story?