In my mind, there is only one lord of film score, and it is John Williams. In terms of prolificacy, variety, emotion and sheer staying power, he is undefeated. So I’m going to talk about the composer that one-upped him.

Howard Shore has been scoring films for quite some time; his first features film was The Brood, back in 1979 (having said that, John Williams started way back in 1958!). He spent the next two decades writing music for many, many notable, famous and oscar-winning films. The Fly, The Silence of the Lambs, Philadelphia, Crash and Gangs of New York all bear his haunting melodies. More recently, he has been responsible for Martin Scorcese‘s masterpiece, Hugo, which is one of my favorite films of the past ten years.

But – poor soul – he had never won an Oscar, and I hate to say it, but I can’t remember a melody or tune from any of these movies. Can you? I remember The Silence of the Lambs opening with some eerie piano music, but couldn’t sing the tune back to you at all. In part, of course, these have all been exceptionally serious films, and such movies can rarely sustain a rousing melody. John Williams, with his plethora of forays into fantasy (Jaws, Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, E.T. The Extraterrestrial…), has had much more freedom in expressing his artistic style.

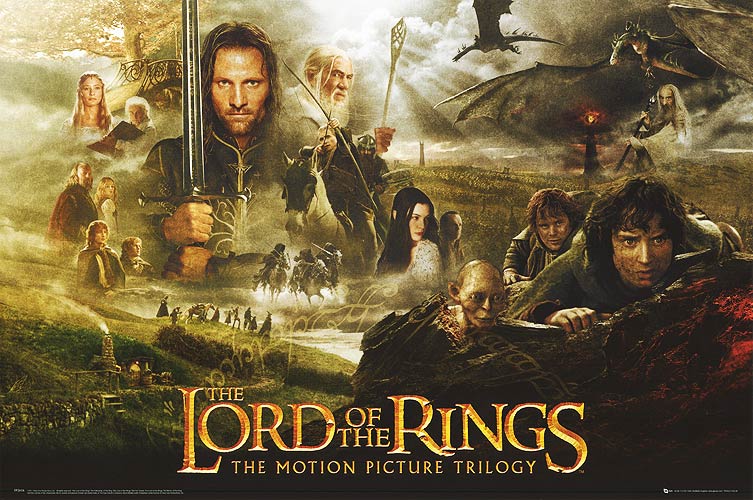

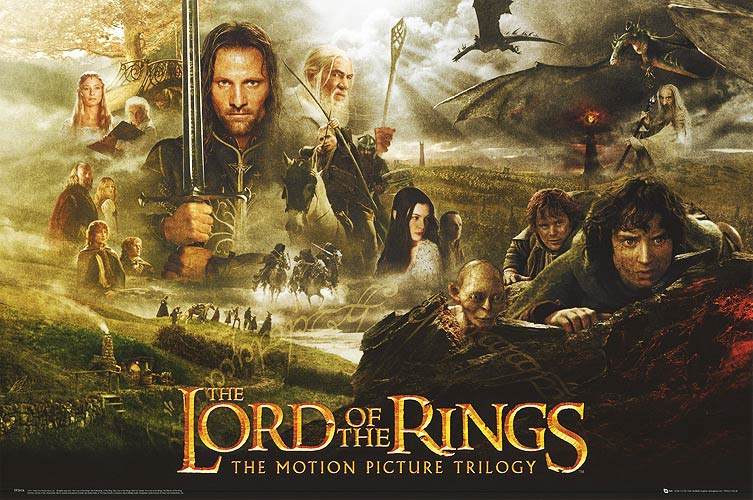

So if the nature of the film determines the expressiveness of the soundtrack, what would this mean for The Lord of the Rings? Peter Jackson brought a depth to these tales that defied expectation, with sweeping landscapes, battles of epic proportions and an impossible attention to detail; there is more Elvish spoken in the film than appears in all three books. What could Howard possibly write that would not only support this monument, but overshadow the film itself and bridge the gap between the image and the audience?

He delved deep, scoured every mote of his musical training and knowledge, released himself from all constraints: and wrote an opera.

For any of you familiar with the programmatic music of the late 1800s, a movement pioneered by Beethoven sought to tell stories through music. The composer would craft a theme for each part of the tale, and the listener would be expected to follow the story by picking up and recognizing these themes. It was Wagner, however, that created the concept of the leitmotif: a very specific and recognizable melody – a tune, as it were – to represent characters, places and events. These might appear on their own, perhaps at the introduction of a new character; they might appear combined with numerous others, building an entire scene and plot, reinforcing the story told through the opera itself.

Now, the application of this concept to film is hardly new; John Williams achieved this brilliantly in Star Wars, of course. Everyone can recall the opening theme, which is used to represent, most often, Luke Skywalker. But can you also remember the Imperial March? Perhaps the force theme (first heard when Luke is looking out over the twin sunsets of Tatooine)? Each of these memorable motifs recurs throughout the films, brought back not at random, but very deliberately to represent specific elements in the film.

So where did Howard Shore go beyond this? He composed nearly a hundred separate, individual leitmotifs for the film, some of the most recognizable being the Ring (heard over the opening titles), the Shire (heard when we are first introduced to Frodo), the Black Riders (quick, low notes on bassoons), Isengard (heavy, descending thirds in the brass), Mordor (high, chromatic brass), Rohan (wonderful, rustic fiddle) and, most brilliant of all, Gondor: horns, playing in the style of hunter’s horns of days past (heard in the most hair-raising climax, musically, of the entire trilogy, when Gandalf is racing up the seven levels of Minas Tirith, desperately seeking the Lord Denethor).

Howard, however, took his multitudinous leitmotifs, and used them in ingenious and subtle ways, signifying the most important changes and climaxes of the tale. Take, for instance, the theme of the Fellowship – heard in full at that famous scene, used in the trailers, where Gandalf appears over the lip of a rocky hill, as the Fellowship, fresh from Rivendell, set out on their quest. This theme is heard abundantly throughout the first film, often heard in its full orchestration. It is also heard throughout the second and third films as well, but: not in full. The theme of the Fellowship is never heard in its complete, orchestrated version again following the breaking of the Fellowship.

Other instances of this ingenuity are equally noticeable elsewhere; Isengard and Mordor have distinct, but complementary, brass themes. When we are shown scenes involving both Saruman and Sauron, these themes are heard together. The Isengard theme is associated also with the Nazgûl, and these two themes are heard prevalently as the goblin army leaves Minas Morgul under the watch of the Witch King of Angmar.

To me, Howard’s score for The Lord of the Rings represents possibly the finest music ever committed to film, both in its scope, inventiveness and sheer beauty. I feel his heart and his soul poured into this score, and if he never betters it, it will remain his crowning achievement. It is inseparable from the film, and from the tale; I cannot read Tolkien’s passages of Rohan without the theme of the Rohirrim passing through my head.

So watch out, John – you might have the quantity, but here, in this instance, Howard has the quality. I believe I could live the rest of my life and never hear such beauty in a film.