There are certain things that ring so of despair that they are instantly recognizable. In life there are such things — death, sadness, old men crying. In art also, there exists an equal dogma of darkness (even the term darkness serves as such an example). The darker of colors — black, blue, crimson — these are colors of despair. They are the colors of things that are frightening — the black of night, the unfathomable depths of the ocean, the terrifying heat of flame, and the letting of blood.

These colors form a great part of our perception of misery and sadness. Winston Churchill famously referred to depression as his “black dog”. Yet even the shading of these colors is significant; when we describe someone as being “blue”, we rarely imagine the pale, soothing blue of a spring sky. Bright red is a color of excitement and joy; deeper tones convey heat and flame and blood.

I think this man might be useful to me – if my black dog returns. He seems quite away from me now – it is such a relief. All the colours come back into the picture.

— Winston Churchill, 1911

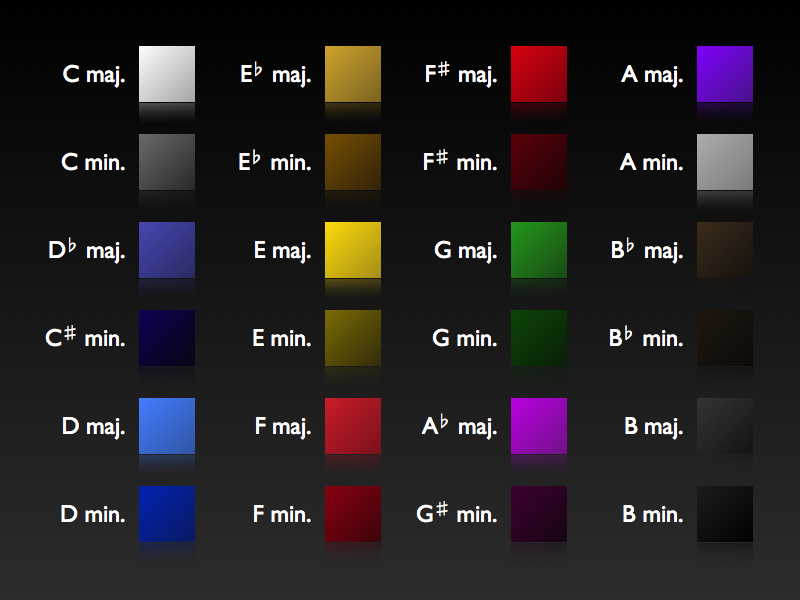

And these tones are carried through into music. Ignoring synesthesia, it isn’t uncommon to think of a song or piece as carrying a particular color. These visual representations of key vary from person to person; if you were to ask any two musicians, you would likely get two completely different descriptions.

My personal key-color relationships. Even ignoring the colors, notice that the minor keys are universally darker than the major ones.

Having said that, there are certain keys that, almost universally represent sadness, anger and despair. As a starting point, these keys are naturally minor. The bright, exuberant major keys — the clean, purity of C major or the homeliness and warmth of E-flat major — rarely suggest any aspect of darkness. The inherent sad quality of the minor key, however, is inextricable.

Part of this is in the psychological impact of the falling semitone; to turn major into minor, the third key of the scale falls by one semitone. The very nature of falling and descent is linked to death (going underground) and sadness (the falling of tears). One of the most heart-wrenching progressions is the fall from the sixth note of a minor scale to the fifth (especially if the root note remains in the bass). A wonderful example of this is the opening of Sotto Vento by Ludovico Einaudi.

However, quite apart from this inherent quality of the minor keys, there is a particular key (or closely related keys) that has throughout the history of western music been used to express the deepest pathos and despair. Countless works have been based on this key, and they are without exception some of the most beautiful, and tragic, pieces of music ever written.

I speak, of course, of B minor (the key that, for me, is represented by the deepest black). There is likely a reason for this; C major, the standard and most oft used key, is above this by one semitone. The shift, the fall from this key of happiness, represents a profound shift from light to dark.

What’s interesting, however, is that this history of this key is not so straightforward. Though from the 1800s onwards B minor because a de facto standard for sadness, it was prior to this rarely used. Instead, the tonally slightly higher key of C minor was used instead. Mozart wrote a beautiful mass in C minor (despite rarely using minor keys in general); one of his best piano concertos is the twenty-fourth in C minor. Later, Beethoven used this key for one of the most famous and furious of compositions: the raging fifth symphony in C minor. He was attracted to this key several times further: his eighth piano sonata, the Pathétique; the third piano concerto (clearly and heavily influenced by Mozart’s own piano concerto in the same key), and the thirty-second piano sonata (one of the last pieces he ever wrote).

Yet something happened in the early nineteenth century that changed this, and suddenly the key of despair dropped a semitone. We began to see works such as Schubert‘s eighth symphony, Chopin‘s third piano sonata, Liszt’s only piano sonata and the wonderful Totentanz, and Brahms’ chamber works (one of the most delicate and beautiful, the first piano trio in B, is in fact half in B minor). And then there was Tchaikovsky. B minor was an epic favorite of this troubled composer, being the home key of his first piano concerto, the beautiful Swan Lake, the furious passages of the Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture, and of course the intensely tragic and heartbreaking sixth symphony, the Pathétique.

Though at first it might appear that there are therefore two keys of darkness, and that the choice of key is down to the individual perception of the composer, it turns out not to be so simple. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, there was no set tonal standard, meaning that different countries, and indeed different orchestras, would have their own definitions of standard concert tonality. In most cases, of course, the tonalities were similar – often differing by one semitone.

And to this day, as western tonalities became standardized (a practice that was only formalized in the 1950s), the key of B minor has assumed reign as the common standard for darkness, and despair.