The grounds of the Van Duyne House, in New Jersey. It has some historic significance, having been used by couriers during the American Revolution.

Tag Archives: History

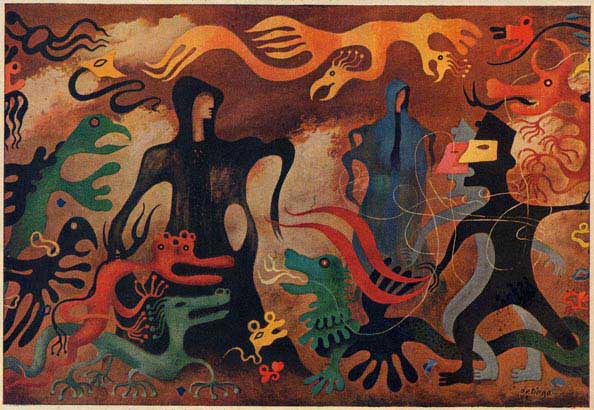

Tales of Despair: Garden of Hell

Some time ago, I wrote about discovering Pieter Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death; a vast, melancholic landscape of horror, with the dead come back to drag the living down to hell. He portrays a hopelessness in death – there is no escape: peasant and king, saints and sinners, all succumb.

As I learned about Bruegel‘s fascination with hell, it brought my attention to the one who significantly influenced his style and subject matter: Hieronymus Bosch. From an earlier generation (Hieronymus died around 1516; Pieter wasn’t born until 1525), he was born and raised in the Netherlands to a family of artists: his father and four uncles were all painters, as their father had been also. In this early stage of the European Renaissance, the Netherlands appeared to be more tolerant of the representation of death, demons and hell – with their frankly grotesque, disturbing and often mind-bending caricatures of men and devils, it is easy to imagine his work denounced as heresy, or worse, the influence of the devil himself.

Though there is no reason to believe his childhood was less than ideal, a great fire in his home town when he was but a boy laid waste to thousands of homes. One can only imagine the terror and devastation of a fifteenth-century village, flames spreading from roof to roof, as men valiantly throw water from buckets onto the ever-blackening homes. Caught in the living hell, thousands must have perished, screaming and burned alive. And when all was over, the horror of stepping through the smoldering ruins, blackened and charred bones lying side by side with the beams of houses. From this, it is suddenly easier to imagine the influence for his work.

One of his best-known works today is the seminal Garden of Earthly Delights (doom metal band Cathedral pay wonderful homage on their album, The Garden of Unearthly Delights). It is a monumental piece, a staggering seven feet high and thirteen feet across, oil painted on wood, with hinges that allow it to be folded closed. Thus separated into three parts, Hieronymus dedicated each third to depicting a stage of mankind’s journey from conception to corruption to death. The left-most panel – the simplest, in terms of content – is dedicated to the garden of Eden, replete with newly-made animals, luscious lakes and fields, and azure mountains in the far distance. Orchards and palm trees sway (did they have palm trees in the Netherlands?), and in the foreground, Adam sits, watching as God presents Eve to him, new and pure and virgin.

Even here, the surreal nature of his work can be seen; while some animals are recognizable, others appear as odd or deformed creatures, including three-headed lizards, deformed snakes, and some creatures that are beyond recognition.

The central panel, twice the width of the side panels, is given over to – perhaps – paradise. It is a busy scene, with nude folk cavorting endlessly far into the distance. Here already, the scene is already becoming unsettling; though at first it appears that the beauty of Eden has grown to accommodate the growth of man, there are signs that not all is well.

Not a man or woman can be seen toiling or working, and in their play, there show the signs of corruption, sin and vice. On the left of this panel there are depictions of good; in the far distance, groups of people can be seen entering upon paradise, among the unadulterated animals we know so well. A couple sit side-by-side on a giant pink sculpture, and a man even flies high above the world on the back of a griffin, holding aloft a branch of peace.

Yet as we move along, things begin to run afoul; men have begun to abuse their power over the beasts, riding them for their own pleasures. At the same time, their very pleasures become more bestial, as the eat from the beaks of birds, and appear even to seek congress with fish.

And of course, in the far right the ultimate symbol of sin: man taking the forbidden fruit.

And so we enter the depths of hell, and it is here where Hieronymus’ true talent – and most bizarre and terrifying imaginations – is revealed. From severed feet to living consumption to grotesque violations, every detail is intended to shock and horrify.

In one corner, a man makes love to a pig, while behind him misers defecate money into a cesspit in which further sinners can be seen drowning. Beside them, a hideous demon gropes an unconscious woman, while a donkey looks on.

Elsewhere, musicians are impaled upon their own instruments, and tormented by the demonic music now passing through their ears.

In the center of the panel, a bisected giant forms the setting for the damnation of gluttons and soldiers alike; men are led into a fiery cavern to feast upon embers and ash, below whom tortured souls drown below the frozen waters. To their right, demons impale, imprison and feast upon soldiers – those who would kill for glory.

But it is at the top of this panel, in the darkest and most frightening place imaginable, that the true despair of hell is shown. Lost in dark fog and shadows, the fires of hell burn high, and men are whipped, burned and massacred. Torn limb from limb, they are thrown into rivers or cast into flames, and always new sinners fall from the world above.

Most heartbreaking and tormented, though, of all this, is a tiny detail at the absolute height of hell: behind the terrible black cliffs, the light of salvation glows – forever unattainable. Despite this, a single, solitary man braves the flames and the heights, desperately seeking redemption. And above him, an angel plummets from heaven.

Tales of Despair: The Fantastic Descent into Hell

Perhaps disheartened by the difficulty of writing an actual opera, in 1804 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) had the bright idea to tell a musical story without the words, and so was born the programmatic symphony. His sixth orchestral masterpiece, the “Pastoral” symphony, was one of the first great musical creations to not just paint a scene or don a mood, but tell, from start to finish, a coherent and structured tale, through wordless music alone.

And it was a phenomenal achievement; through five intertwined movements, we are taken through the experience of the composer as he travels to an idyllic countryside, breathes in the beauty and serenity of the pastures and streams, and revels in the joyous dancing of the country folk. In a dark turn, we are overcome by a terrifying and violent storm, threatening to ravage the countryside, until finally it passes, and we rejoice with the shepherds. The story is, admittedly, rather naïve, but Beethoven was one of the great advocates of Goethe‘s humanism at the time, desperate for the belief that man was a better creature, and could aspire to beauty and greatness.

As the world moved forward into the romantic era, the youthful idealism became tainted with the dark reality of industrialism, war and poverty. Stories continued to be told, but they became ever darker. Composers and pianists, the rock starts of the nineteenth century, became corrupted by their popularity. Hector Berlioz (1803 – 1869), the infamous French composer, wrote many of his greatest works under the heavy influence of opium. In fact, perhaps his greatest tribute to Beethoven – a twisted retelling of his tale of beauty and serenity – is the Symphonie Fantastique, in which that very drug is the catalyst for a descent into murder and madness.

Being a child of the romantic era, Berlioz was infused with the passion and impetuosity of many of those of his generation, and he found himself infatuated with several women in his life. One of these, an Irish actress called Harriet, caught his fierce attention in Romeo and Juliet, and she became the inspiration for what is today perhaps his most enduring work.

Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique is, as was Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, a song with a tale to tell. Our young musician, in a dream of passion, discovers a woman who embodies his every ideal, and cannot rid her from his mind. He is delirious, love-struck, despairing and joyful, and sees her in his mind every waking moment. These thoughts consume him even as he passes through life – at a ball, a festive, joyous occasion, he cannot see the lights or the music. Wandering in the fields, by the brook and past the shepherds, he cannot but brood on his terrible loneliness. He wishes – hopes – that he may soon not be alone, but thoughts of betrayal of evil creep through his mind.

And then, the story takes a dark turn, and does not return. Convinced his love has forsaken him, he poisons himself with opium, and as he lays dying, he is plagued with the terrifying dream that he has murdered his only beloved. Powerless from the drug, he watches helplessly as he is captured, and led to the gallows. The crowd looks on, he cries out in despair – and, as the guillotine’s blade descends, he sees her in the crowd – alive.

And it does not end there. Dead, he finds himself transported to hell, lost in the midst of a witches’ Sabbath. Shadows, demons, sorcerers dance sickeningly around him, taunting and teasing him in his own death. And then – horror upon horror – he sees that she is a part of the diabolical gathering, that she is dancing to his death with the witches. As the bells of his death sound, the terrible creatures conspire to mock god, dancing over the ancient music of his wrath, and all is lost to perpetual darkness.

Inspired by the beautiful Harriet, Berlioz went on nonetheless to become engaged to a Camille, instead. When she spurned him, he raced to Paris, seeking to murder her, her mother and her fiancé. Eventually, when this plan failed, he returned to Harriet – and there, he discovered the painful truth behind infatuation. The two wed for a mere two years.

Berlioz would go on to produce one of the most famous renditions of the legend of Faust, who sold his soul to the devil. He separated from Harriet, and though he continued to provide for her for the rest of her life, she died not long after from severe alcohol abuse. His mistress, whom he eventually married, died eight years later. A girl for whom he had affection, only twenty-one years old, died also, and Berlioz was left with nothing but his grief.

At the age of only sixty, he began, in his despair, to wish for death, and not long after, he was stricken with violent abdominal pains. The pains soon grew and spread, and in the end, consumed him. On his death bed, he spoke these final words:

Enfin, on va jouer ma musique.