Very few things in this world are perfect. Our jobs, our relationships, our partners and ourselves – these are all subject to the (often enormous) imperfections of life, and for the most part we live our lives content with – or at least ignoring – this fact most of the time.

It doesn’t help that perfection is highly subjective; one person’s ‘perfect’ book might be another’s most-loathed prose ever. I saw a post on Reddit the other day asking for opinions on the ‘perfect’ movie; answers ranged from Star Wars to The Grapes of Wrath. Many people agreed, others disagreed, and some simply suggested their own ‘perfect’ movies.

Unfortunately, despite knowing full-well that perfection is unattainable, many of us are perfectionists anyway. I know I am – or at least, I used to be – and I know many others who share this trait with me. For me it varies from subject to subject, as I suspect it does with many; those things I’m most passionate about are the things I have the highest expectations of. Projects that mean a lot to me come with an elevated need to be as close to perfect as possible.

But here’s the thing: perfection, whilst not technically impossible, depends entirely on the scale at which one is assessing the thing claiming to be perfect. My books, for instance, are far from perfect. They contain numerous flaws, plot holes, typos (despite intense editing), and passages that, in retrospect, I wish I had written differently.

But let’s zoom in a little more. Take the following passage:

“And so it was with a lighter heart that Brandyé Dui-Erâth began to walk away from the river and away from all he knew. And so it was that, unknown to him, Darkness followed behind and laughed.”

Satis – The Redemption of Erâth: Consolation

These are the final lines of the first Redemption of Erâth book. For the style and setting, to me this is as perfect as I can make it. I adore this lines, it took me a long time to come up with them, and they close out a book of sadness and despair beautifully. These two sentences are, to me, perfect. Better still is that they form the last paragraph of the book, because it leaves the reader feeling both sadness and hope.

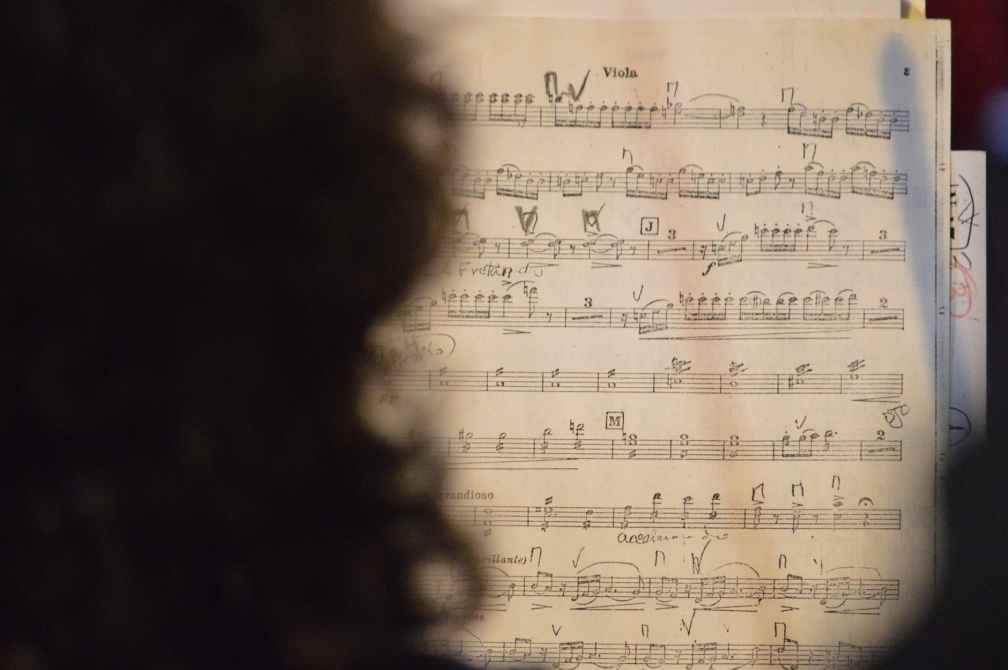

One of the things I’ve been doing for my alter-ego’s upcoming young adult novel is writing songs to go with it. I’ve put down the notes, played with the sound, and recorded some vocals. Again – far from perfect. Yet some of the songs I actually really enjoy. My singing isn’t great, and the guitars sound a little artificial at times, but there are the odd ‘magic moments’ that really make me think, wow – I did a good job.

The problem is that minute perfection is exponentially difficult to scale. One note, one sentence, can be perfect. But art is made of millions of paint strokes, and not every one of them can be perfect. And as artists, we have a choice: we can go back and change and improve to no end … or we can just release the damn thing and let people enjoy imperfection.

After all, a song with perfect timing will not only sound like it’s being played by a robot – a robot is the only thing that could play it perfectly. Imperfections make us human, and some of the best recordings and works of literary genius are all the better for their imperfections; they help the rest stand out all the more as the genius that it really is.

Besides – most people will never notice.